A quick tour to Russia’s oldest city revealed more than grand architecture and a good opportunity for a few photographs – it revealed some of the depth and horror buried in Russia’s past.

A quick tour to Russia’s oldest city revealed more than grand architecture and a good opportunity for a few photographs – it revealed some of the depth and horror buried in Russia’s past.

Each year on February 23, Russia celebrates the Defender of the Fatherland Day. This February events in Ukraine were far from my mind – my thoughts were on previous conflicts with sobering thoughts about what happens when defenders fail.

The celebration was established early in the establishment of the Soviet Union to celebrate the formation of the Red Army. However the celebration falls singularly close to the date of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk which was seen as an embarrassing loss and concession by the newly formed Soviet government, giving away large areas of former imperial territory, including much of the Ukraine.

Members of the Russian Communist Party hold a rally in front of a statue of Lenin to celebrate Defender of the Fatherland Day

To celebrate this day I took a tour to one of Russia’s most ancient cities, Veliky Novgorod. After an ungodly early start we clambered aboard a minibus and were given a lively commentary by a local historian as we flew south along the highway. The road roughly passed along the line of the eastern front in World War II and the guide told the story of the General Vlasov’s Second Shock Army which was engulfed attempting to break through the line at this point to relieve Leningrad. The unprepared army made the attempt on the line south of Leningrad with the intention of capturing key German positions along the Volkhov River and then working their way back to Leningrad in what would have been a clean-up operation. Soviet forces managed to break the German line and cut their way deep into German held territory. The break was only a couple of hundred metres wide and the Soviet forces found themselves under cross fire with insufficient support and supplies. The location of Soviet troops could be seen from the air by the barrenness of vegetation as the Russians ate bark and leaves in an effort to survive. The attack began on January 7 1942 as part of the Lyuban offensive and the last of the Soviet soldiers were killed in May as they made a final attempt to escape.

On the landward side the brickwalls of the Novgorod kremlin were protected by a deep trench fed by the Volkhov River

A 3.5 hour drive took us to the northern outskirts of Novgorod and we drove past decaying and broken down wooden buildings and then past a series of new construction sites. The population of the city is about 300,000 and drops each year, so it’s hard to see where the demand for new houses is, as the city itself doesn’t seem to have much of an economy. One can understand why inhabitants would want to move out of buildings which look like remnants of the 19th century, but where does the money come from to enable them to relocate, unless it is St. Petersburg refugees fleeing the rat race of the big city.

The city is one of Russia’s oldest and is known for its independence and for being a republic. Although dating cities is always a matter of controversy, the general belief is that Novgorod was founded in 862 A.D. though archaeological evidence suggests that it may have been founded in the 10th century – it begs the question though, when is a city founded and when is it simply a collection of buildings?

Located about 150 kilometres south of St. Petersburg the city grew rich as a staging post for trade throughout the Baltic. Sitting at the head of the Volkhov River it had access to the main trade routes running through Russia and trade with cities of the Hanseatic League.

Being a wealthy trading city, Novgorod was able to dictate terms to most military leaders and this gave it a higher degree of autonomy and independence from the ruling nobility than other Rus cities and during the early stages of Rus history it was the second major centre of Rus culture, along with Kievan Rus.

An early Russian log house. These houses included a barn so that animals could be kept warm and near at hand during the perishing winters. The entire extended family of about 20 people lived in a single house. This house is located at the Vitoslavlitsy open air museum at Yurevo Village close to Novgorod

However, its relatively large population and infertile soil – the territory around the city was largely swamp which helped protect the city from attack but didn’t assist agriculture – led to a dependence on more productive areas of Russia – making it subject to Vladimir and Suzdal. While the Golden Horde never seized the city – the horde stopped about 100 km from the city – it did pay tribute to other princes during the Mongol period, making it a vassal of other Mongol vassals, presumably paying people off was an easier option than open resistance.

Under Alexander Nevsky the city participated in wars with both the Mongols and the Swedes. Later it came into conflict with Moscow and after a series of wars finally lost its influence in the early 16th century after a plague went through the city killing much of the population. A fire followed shortly after the plague and destroyed much of the trading goods.

The city also suffered under the reign of Ivan the Terrible. The conqueror of Kazan who won his title ‘terrible’ for his wars against the khaganates went on to justify the title for his own populace. Establishing the Oprichniki, a forerunner of such organisations as the Cheka and KGB, this private army held Russia in terror during its existence (1565-1572). They were given the role of sniffing out treason. They dressed in monk’s habits and tied dog heads to their horses to symbolise their purpose.

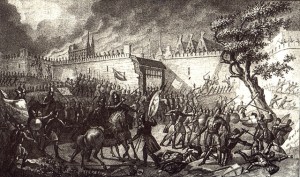

In 1570, Ivan the Terrible was in the middle of fighting the disastrous Livonian War (1558–1583) and running out of money, when the Oprichniki brought evidence that the city of Novgorod intended to transfer its allegiance. There are rumours that this evidence was faked by an adventurer who was punished in Novgorod and by providing faked documents sought his revenge. Most likely it served as a convenient pretext for plundering the city. The subsequent sack of the city that took place in January 1570 is claimed to have lasted five weeks, with some estimating casualties to be around 10,000 to 15,000. The city at the time is thought to have had a population of less than 30,000. The main bridge out of the Novgorod kremlin is called Bloody Bridge in memory of the people thrown from it. It is said that there was so much blood that the river melted.

Battle of Narva (1558) during the Livonian War (1558-83). Narva is now a border town on the Russian-Estonian border.

The sacking has left its mark on the city. It signalled the end of Novgorod’s greatness and is memorialised by a pigeon attached to the cross of the main cathedral in the kremlin – St. Sophia Cathedral. Legend has it that the pigeon landed on the cross during the sack of Novgorod and looked down to see the massacre which was taking place. The bird was so shocked by the scene it was petrified. However, there is more to the story of the pigeon than meets the eye, as you will discover below.

The cathedral was built in 1045-1050 by Yaroslav the Wise and is one of the oldest churches still in use in Russia. According to Byzantine tradition the Cathedral of St. Sophia is a square construction about 27 metres by 34 metres and 36 metres high, covered in frescoes. While a couple of frescoes have been found and recovered from the period of the church’s construction most frescoes are repainted every generation or so and although they remain faithful to the traditional style of the orthodox fresco painting – it is clear when you compare a modern fresco with its ancient counterpart that modernity still finds its reflection in painting, the faces look different – they mainly appear to be happier.

The relic that makes this church particularly holy is an icon of Mary which protected the city from sacking in the 12th century. In 1170 the city was besieged by the forces of the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Andrei Bogolyubsky. His forces were larger and superior to those of the merchant town and in desperation the townspeople began praying to the icon. On the third night of the siege the bishop heard a voice instructing him to place the icon at a certain position on the siege wall. The besieging forces fired thick volleys of arrows at the defenders, one of which struck the image of Mary in the eye, and a tear appeared. She turned her face towards the defenders and the besieging forces, terrified, threw down their arms and fled from the battlefield.

The cathedral also houses the bones of Yaraslavl the Wise and his holy mother – their story sounds like it was cribbed from a retelling of Constantine – one wonders how original some of these early historians really were.

The other curiosity about this cathedral is the presence of another cross with a pigeon by the altar. During World War II, Novgorod, including the kremlin was captured by German forces. When the Germans were finally driven back, the cathedral was missing its cross. Fifty odd years went by, the Soviet Government largely restored the kremlin and parts of Novgorod – although other parts look like marauders pillaged the territory only yesterday – a new cross was put on the cathedral to replace the old one which disappeared the way gold seems to disappear in wartime. Eventually, the Iron Curtain was pulled open and tourists started visiting the city. One day a tour guide was talking to a Spanish tourist about the cross and the tourist responded along the lines of: “This is very interesting because we have a cross just like that in Madrid.”

A bronze sculpture celebrating the millenium anniversary since the founding of the city – and a millenium of Russian statehood.

Inquiries were made and it was discovered that the cross in Madrid was indeed taken from Novgorod during World War II. Serving alongside German forces in Novgorod was a unit of Spanish volunteers, as they were withdrawing they decided it would be a pity to leave a Christian cross in the hands of atheist forces and took it home and used it to adorn one of their own churches in Madrid. In total about 45,000 Spanish volunteers served with the Germans, mostly on the eastern front.

When Soviet forces finally retook Novgorod, not only did they find the city cathedral missing its stone pigeon but they found a lifeless city. In total 30 people survived the German occupation.

On the day of the Defender of the Fatherland, the visit was a solemn reminder of what defenders are prepared to do in the name of the Fatherland.

Be sure to like Intrepid Adventure on Facebook and check out Peter Campbell’s latest books on Amazon.com.

Copyright © Peter Campbell 2014, www.intrepid-adventure.com