The winds that chill New Zealand’s winter rush across 2500km of sea from Antarctica. In winter, Antarctica is the coldest place on Earth, a place of darkness. Scientists work there throughout the year. Air support enables them to turn an inhospitable land into a laboratory where they research climate change, biology, oceanography, and an innumerable number of other subjects. Peter Campbell explores the rigours of life with Scott on the Frozen Continent, 100 years ago.

In 1911 there was no air support. There were no icebreakers, and no GPS to fix your location on Google maps. Those who ventured south faced hardship, cold and death. They had no modern materials which help shield us from the ravages of cold. No lightweight equipment to make their task easier. Audacious and innovative, they sailed to Antarctica and dragged their equipment behind them on sleds carrying out scientific research in spite of weakness, illness, and cold.

Despite our relative proximity to the Frozen Continent and its influence on us in terms of weather and ocean patterns, it is a land of which we have little comprehension and is hard for us to contemplate the horrors of its exploration. Hunger, cold, scurvy, unpredictable ice-floes and concealed crevices menaced those who explored the territory. The lack of set landmarks and the proximity to the magnetic South Pole made navigation tricky and in many cases, the explorers seem to have returned to base more by providence or luck than by skilled compass and sextant work.

Although their deeds have largely been forgotten, Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen are still household names for many. Amundsen is remarkable for being the first man to the south pole. A skilled explorer, he was the first to travel through the North-West Passage on a route which some 40 years previously had cost the lives of English explorer John Franklin and the rest of his crew.

Amundsen poses at the South Pole

Amundsen’s aims were those of an adventurer. He wanted to be the first man to the South Pole and his expedition was organised to achieve that end. Scott’s expedition was scientific and despite knowing of Amundsen’s presence in Antarctica, he refused to lower the priority of scientific research in order to be the first man to the South Pole. As Scott wrote in his journal:

“One thing only fixes itself definitely in my mind. The proper, as well as the wiser, course for us is to proceed exactly as though this had not happened [the arrival of Amundsen in Antarctica]. To go forward and do our best for the honour of the country without fear or panic.”

Amundsen freely admitted that his expedition was different in nature from Scott’s.

“The British expedition was designed entirely for scientific research. The Pole was only a side-issue, whereas in my extended plan it was the main object.”

Scott’s vessel, the Terra Nova, departed Lyttelton on 25 November 1910 with 65 men, including 17 officers, 11 scientists, and 27 sailors.

After numerous days caught in pack ice, they arrived at Evans Bay on January 4, 1911. Their hut nestled in at the head of a bay with views towards Mt Erebus and Mt Terror, named after vessels of an expedition led by James Ross in 1839 to 43. Having established a base camp they began making depots along the route to the South Pole for the march the following summer. Some scientific activity was also performed during this period but was frustrated by ice conditions.

An astonishing month long journey was undertaken in mid-winter from June 27 to August 2. One of the failings of Scott’s Discovery Expedition to Antarctica in 1901 – 1904 was the failure to bring back emperor penguin eggs. The emperor penguin is unique. It is the most primitive of penguin species as well as the largest. It was thought that possessing an egg with an embryo in it would show the bird in its previous stages of evolution and would enable scientists to prove the missing link between birds and reptiles. The chief scientist of the expedition was Edward Adrian Wilson, a participant of the Discovery Expedition. He estimated that the emperor penguins must lay their eggs in July. This meant the scientists had to make a trip to Cape Crozier from Evans Bay in mid-winter. It was a journey of only 110 kilometres but took 19 days to reach the colony. Apsley Cherry-Garrard described in detail the horror:

“It is desirable that the body should work, feed and sleep at regular hours, and this is too often forgotten when sledging. But just now we found we were unable to fit eight hours marching and seven hours in our sleeping-bags into a 24-hour day: the routine camp work took more than 9 hours, such were the conditions. We therefore ceased to observe the quite imaginary difference between night and day, and it was noon on Friday (July 7) before we got away. The temperature was -68° [-56degC] and there was a thick white fog: generally we had but the vaguest idea where we were, and we camped at 10pm after managing 1¾ miles [2.8km] for the day. But what a relief. Instead of labouring away, our hearts were beating more naturally: it was easier to camp, we had some feeling in our hands, and our feet had not gone to sleep. Birdie swung the thermometer and found it only -55° [-48degC]”

But his descriptions, as those of most Antarctic expeditions, do not describe the physical toll that the cold worked on the body. At -30degC it only takes half a minute for the naked hand to lose sensation.

Wilson sketched landscapes so that he could paint them in water colours during the winter months:

“He sketched quickly with bare fingers and mittened hands, jotting down the outlines of hills and clouds, and pencilling in the colours by name. After a minute, more or less, the fingers become too cold for such work, and they must be put back into the wool and fur mitts until they are again warm enough to continue.”

During this trip their sleeping bags were frozen and had to be thawed each night so they could be prised open and slept in and sleep was fitful.

“For me it was a very bad night: a succession of shivering fits which I was quite unable to stop, and which took possession of my body for many minutes at a time until I thought my back would break, such was the strain placed upon it. They talk of chattering teeth: but when your body chatters you may call yourself cold. I can only compare the strain to that which I have been unfortunate enough to see in a case of lock-jaw. One of my big toes was frost-bitten, but I do not know for how long. Wilson was fairly comfortable in his smaller bag, and Bowers was snoring loudly. The minimum temperature that night as taken under the sledge was -69° [-56degC]; and as taken on the sledge was -75°[-59degC].”

In such conditions, fingers blistered and the water inside the blisters froze. The constant pain and constant tasks wore on the mind as much as they did on the body.

“We got no respite. I found it best to refuse to let myself think of the past or the future—to live only for the job of the moment, and to compel myself to think only how to do it most efficiently. Once you let yourself imagine….”

On the return a blizzard blew away their tent and resigned to a freezing death the men marched on. Cherry-Gerrard commented on their mood as they faced death.

“When, later, we were sure, so far as we can be sure of anything, that we must die, they were cheerful, and so far as I can judge their songs and cheery words were quite unforced. Nor were they ever flurried, though always as quick as the conditions would allow in moments of emergency. It is hard that often such men must go first when others far less worthy remain.”

And on contemplating his own death he wrote not without some humour:

“I had no wish to review the evils of my past. But the past did seem to have been a bit wasted. The road to Hell may be paved with good intentions: the road to Heaven is paved with lost opportunities.”

After two days and nights they managed to retrieve their tent and made the return journey, bringing with them three emperor penguin eggs, despite falling in a crevasse at one stage when a snow bridge collapsed beneath them.

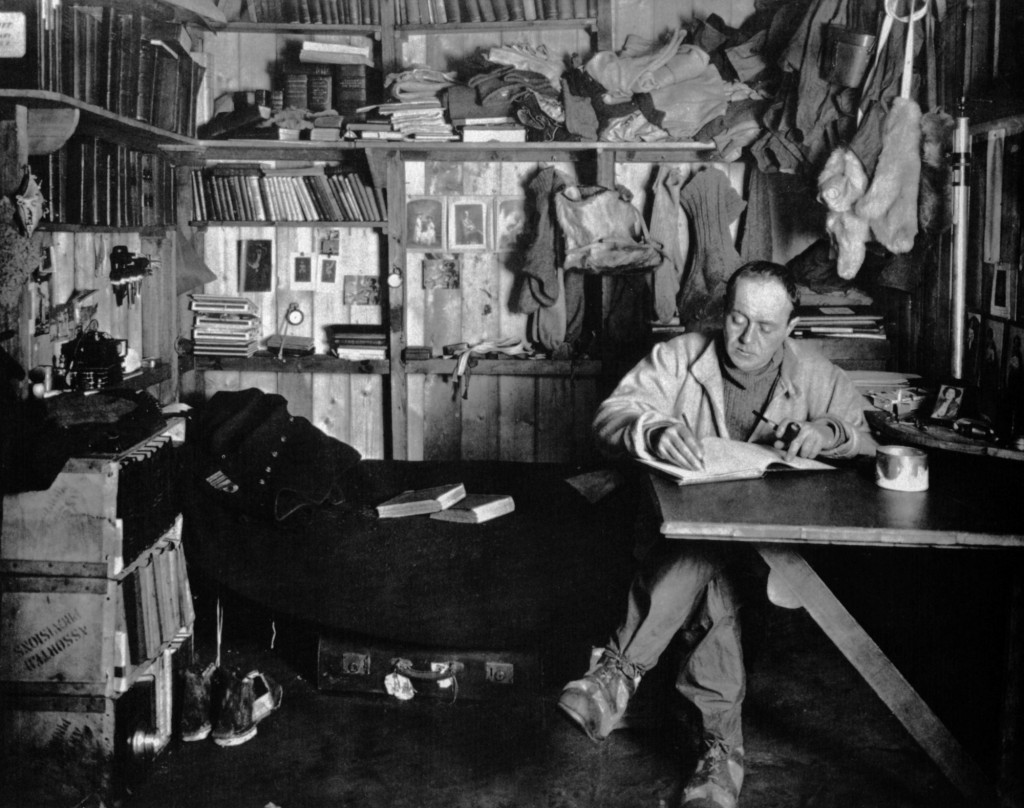

The breadth of activities including scientific research, sketching, writing, delivery of lectures and dramatic performances in addition to the physical endurance and hardship which the explorers underwent shows remarkable talents, education and strength of character. Apart from the journey to Cape Crozier, the men relied on their own ingenuity to entertain themselves throughout the winter while they were confined to a single building which was 15m by 7.7m, accommodating the 24 men who comprised the shore party.

The lectures were not only scientific in nature but were also descriptions of countries and regions where the men had served either with the navy or army, or had conducted scientific research.

One such lecture was delivered by a Meares, whose lecture and character Scott described in his journals.

“He had no pictures and very makeshift maps, yet he held us really entranced for nearly two hours by the sheer interest of his adventures. The spirit of the wanderer is in Meares’ blood: he has no happiness but in the wild places of the earth. I have never met so extreme a type. Even now he is looking forward to getting away by himself to Hut Point, tired already of our scant measure of civilization.”

It was after this winter that Scott, on 24 October 1911, set off for the South Pole. Sixteen men were to travel south and the final leg was to be made by a group of four. Of those four none returned. The story of their trip was preserved in their journals which were maintained throughout even as the men weakened.

It was after this winter that Scott, on 24 October 1911, set off for the South Pole. Sixteen men were to travel south and the final leg was to be made by a group of four. Of those four none returned. The story of their trip was preserved in their journals which were maintained throughout even as the men weakened.

Five months after departing Evans Bay, caught in blizzards and out of supplies, Scott, Wilson and Bowers died on 29 March 1912, 7 km from a supply depot.

The poles were the last territories to be explored. On the extremities of the globe, they offered no riches and no comforts and made poor pickings. The Antarctic expeditions were trips into a harsh, unforgiving and fickle land, which promised only hardship. Despite these hardships Scott wrote in one of his last letters when he knew he was dying:

“What lots and lots I could tell you of this journey. How much better has it been than lounging in too great comfort at home.”

This article has drawn on the following accounts by Antarctic explorers:

- Scott’s Last Expedition, by Capt Robert Falcon Scott

- The Worst Journey in the World, by Apsley Cherry-Gerrard

- The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram,”1910 – 1912, by Roald Amundsen

Be sure to like Intrepid Adventure on Facebook and check out Peter Campbell’s latest books on Amazon.com.

Copyright © Peter Campbell 2014, www.intrepid-adventure.com